ESSAYS AND ANECDOTES

The Hat

Every hat holds a story, and the experiences of the owner show through with little explanation.”

--William Reynolds & Rich Rand, The Cowboy Hat Book

You couldn’t miss the hat. It rested on top of the horn of Dad’s old saddle that was in turn cinched to the horse that my brother had arranged to have at the services outside the old stone church in downtown Colorado Springs. As friends and family filed into the sanctuary, the hat atop the old saddle was one last reminder of the man and his legacy. Gray, weathered and oil-stained from years of rough use, it seemed at once durable and timeless and yet fragile as a feather in the wind. How many thunderstorms, blizzards and droughts; how many crisp and colorful fall mountain days; how may hot summers on the eastern plains had it witnessed? Plenty, I would say. Just like the man whose life we celebrated that day, the hat deserved some rest.

The hat wasn’t the ugliest I had ever seen, despite the wear and tear. For an old hat, it had character and decency. Not that ugly hats mean a lack of decency. Some of the finest men I have known insisted on ugly, worn-out hats. Some of the meanest men I’ve known wore perfect cowboy hats. The story is in the hat, but you have to be patient to sort out the tale.

I never owned a cowboy hat long enough to develop the real patina of a story in it. I owned more straw cowboy hats than felt ones, and that in itself was a mistake. Today, straw hats are ubiquitous, but before mid-century, felt hats were the rule summer and winter and everything in between. Straw hats are cheaper, and some say they are more comfortable in our ever-hotter environment, but nothing really beats a good felt hat for protection from the elements – and that is the real purpose of a hat. I can hardly tell the difference between a felt hat and a straw hat in summer. Both get hot. But if it rains, a wet straw hat will never recover from a good soaking. A felt hat may look bad, but it will come back strong with a little care. Recovering from storms can make all the difference in your life.

Unlike my father and my grandfather, I am not likely to be remembered for my hat or for how I looked in my hat. The oil, dust and creases won’t appear, and I don’t expect that anyone will bother to put my hat atop an old saddle (even if I had one) on a sentry horse at the entrance to my funeral. I suspect folks are likely to remember me wearing an old fedora with a sketchbook under my arm. That’s okay with me. We all have our own symbols in life, and our own history written in those symbols. Those symbols remind us of who we are and how we got there. Every hat holds a story.

Dad's old felt cowboy hat

Essays and Anecdotes

Horses and Mules

There is nothing better for the inside of a man than

the outside of a horse. -- Winston Churchill

Bill was fed up to here with horses. “The thing about horses is this—they just sit around all day with nothin’ to do except figure out how they are going to kill you.” I guess I have to agree. Not that every horse is a killer at heart, but their strength and size can be accidental weapons of mass destruction. Presented with the slightest bit of perceived danger, the natural instinct of a horse is to put as lot of distance, and fast, between itself and the threat—over, under or through whatever stands in their way—and that means you, your dog, your truck, your wife or your baby child. In the blink of an eye, you can have twelve hundred pounds of flying flesh and hooves coming straight at and through you. Woe to anyone in the way. Then, just as quickly as this drama all began, that horse will stop about a quarter mile away, put his head down, and peacefully graze as though nothing had ever happened; and start thinking again about how to kill you.

A mule, on the other hand, doesn’t try any of that nonsense. He can be cantankerous and ornery, but more often is just patient and tolerant—sullen but not mutinous—a classic case of internalized self-superiority over an equine world in which he is viewed as mongrel minority. He too, could do a pretty good job of killing a cowboy, but it is not as though he sits around all day thinking about it. No, the cowboy world and its mythical extension to the world of horse-mounted knights, is of no particular consequence for the mule. Don Quixote may have tilted at windmills on a horse, but Sancho Panza’s mule had more sensible things to do. The mule knows that he is the better beast—smarter, safer, more sure-footed, stronger, tougher and longer-lived than any horse—and his obstinacy is simply a reflection of knowing—at all times—what is best. A horse will obediently start down a trail that is too rocky and too narrow if his rider gives him a spur in the ribs—and he will take the cowboy with him when they both eventually tumble down that trail. A mule will sort out the trail, determine that it is folly to proceed, and refuse to move, unless it is to back off or turn around, leaving an oblivious cowboy flailing away with spurs and stick and yowls and slaps and curses about that “damn stubborn mule.”

Mules are a perfect example of something geneticists call “hybrid vigor.” Born of a donkey father and a horse mother, the mule turns to be more patient and hardy than mom, and less obstinate and more intelligent than dad. As Charles Darwin observed:

The mule always appears to me a most surprising animal. That a

hybrid should possess more reason, memory, and obstinacy social

affection, powers of muscular endurance, and length of life, than

either of its parents, seems to indicate that art has outdone nature.

As beasts of burden, mules could pack more pounds for their size, for longer distances, and over tougher terrain, than any horse. They also ate less and tolerated heat, insects and dry weather much better than a horse. Their hooves are harder and their hides are thicker than a horse. When the Pacific Coast Borax Company needed to haul tons of mineral out of Death Valley over 200 miles of harsh desert to the railhead at Mojave, they didn’t choose a team of 20 horses. The feed and water needed for horses would have been about all they could have hauled. No, they chose a team of 20 mules. Mules, not horses, were the essential mobility machines for the US Army right through the middle of the last century; and the respect and admiration they earned on the battlefield translated to hundreds of thousands of farms, mines, and factories across the country during its great westward expansion.

Grandpa rode a mule named Marilyn, and she was a tall and beautiful bay jenny with a gentle disposition except when it came to horse trailers. Grandpa loved that mule, but he could also dish out tough love when it served him (and that went for grandkids and mules alike). By and large, Marilyn was a compliant and pleasant companion, but when it came to a horse trailer, some kind of devil moved in to possess her.

Horse trailer horror stories are legend in the cowboy world. When it comes to frustrating, dangerous, hilarious, humbling situations—nothing beats a good horse trailer story. Something about the dark unknown reaches deep into the psyche of a horse and stirs a primal fear of stepping up. What’s the deal? There is food and a free ride waiting inside. There might be green grass and bubbling streams waiting at the end of the road. Nobody will be on his back for a few hours and the rhythm of the road might temp him into a standing snooze. But time and time again, a horse will take a stand and resist all your curses, whips, kicks, pulls and pushes to move him in. Even a couple of 200-pound cowboys are no match in that contest against 1,200 pounds of stubborn horseflesh.

As I said before, when a mule decides that danger lurks ahead, they become the most immoveable object imaginable. Most times, they are smart enough to sort out real danger from perceived threats. But sometimes the scary depths of an open trailer fill a mule’s mind with thoughts of bear caves. Or perhaps Marilyn just had bad eyesight. Whatever the reason, Marilyn decided that she was not going to set foot in that trailer. In final desperation, and some not inconsiderable anger—that I had witnessed before, for sure—Grandpa went to the cab of the truck and pulled out a gun. My eyes were as wide as saucers, and I thought, “My god, he is going to kill Marilyn right here in front of me” and then, my thoughts raced forward to the bloody struggle to load her carcass into the trailer. Then I noticed that the gun he had retrieved was not the 30-06, but my BB air gun. Grandpa calmly moved around to get Marilyn’s ass in full view, and he hollered to my dad “OK, Charlie, when I pop her in the butt get ready to haul her in and tie her down.” My dad tightened his grip on the halter rope that was strung out from Marilyn’s nose to the front of the trailer and dug in his boot heels. I could tell by his face that he didn’t know whether he was going to be backpedaling fast or hurtled face-forward into the side of the trailer. It was not clear how Marilyn was going to react to BB’s stinging her rear. I would have preferred to just retreat a to a safe distance behind Grandpa and avoid the entire inevitable mess, but I was expected, in my puny 8-year old frame, to swing that trailer door closed if and when Marilyn launched herself in. I knew that if Marilyn hopped in, she was just as likely to realize her folly and try to kick and buck her way back out, and that I would be on the other side of that action, trying to keep a metal swing-door between me and certain death. Not a happy prospect for an 8-year old, but Grandpa had commanded it, and as my dad and I knew, when the Chief commanded, you obeyed.

“Pop…pop…pop!” went three shots in quick succession. Either Marilyn was so thick-skinned that she couldn’t feel the little pellets, or it took a long time for the pain signals to reach from her hindquarters to her brain, but for a moment nothing happened. Determined, Grandpa pumped the rifle twice and fired off three more stinging BB rounds. Marilyn jumped like a March hare, clearing the lip of the trailer and into the front of the trailer in a single bound. Dad was so surprised that he fell backwards trying to take up the slack. Grandpa commanded action. “Kenny, goddammit, push the door closed!” With the help of a little adrenalin, all 60 pounds of me sprang into action, and with a mighty shove, I swung that gate into position and braced myself for what I was sure was going to be disaster when Marilyn came to her senses and decided to back out of that trailer in a hurry. But it didn’t happen. Once in, and tied down, Marilyn decided not moving was the right thing to do, and Grandpa calmly walked up and slid the latch down to secure the poor beast into her imaginary hall of horrors. To my surprise, there didn’t seem to be a shred of evidence of the six BB pellets shot into her butt. Either her hide was so thick that they ricocheted off (a good bet, since it is well-known that a mule’s hide is harder than a horse’s), or they were buried somewhere in that hide and hopefully wouldn’t amount to any more inconvenience to her than a bad deerfly bite.

Marilyn outlived my Grandpa by a number of years. She went on at least ten more trail rides with my dad before she went to her “final pasture” after 30-plus years of strong and steady service. Marilyn’s younger buddy was Bluebell, a smaller gray spotted mule who was reputed to be a reject from the Army mule brigade, and who somehow ended up in Grandpa’s good graces and soon became Marilyn’s “best friend forever”, so to speak. Dad rode Bluebell on several Range Rides. When Dad finally became Marilyn’s rider, my horse-riding days came to an end, and I was drafted to ride Bluebell on a few Range Rides just to keep Marilyn company. My brother Ron escaped the mule shaming entirely, for by the time he was riding, both Marilyn and Bluebell were gone, and Dad never insisted that Ron or I had to ride mules on the Range Ride. But dad had already become a life-long muleskinner.. After Marilyn died, he had a multi-decade bromance with a small bay jack mule named Barney. Those like my dad who rode and loved mules couldn’t be bothered with fancy names and wouldn’t be shamed or persuaded to trade in their mounts for more conventional rides. They rode the beasts they loved, and the beasts loved them back.

I never rode another mule after my last ride on Bluebell in 1972. I rode some good horses, and a couple less good. There was a quarrelsome chestnut Arabian, a gentle Palomino quarter horse and a sometimes trail-skittish red chestnut named JJ that belonged to my uncle Willy. Later on when I would make a ride only every 5 years or so, Ron would lend me his beloved Roanie, one of the best horses I have ever ridden. Roanie was as close as a horse could get to a mule’s calm temperament and smarts. As for the orneriest horses I have ever known, two make the honors list. The first was a spiteful little Shetland pony that my grandfather gave me at Christmas in 1958. The second was a spirited young Galecino pony aptly named “Diablo.”

I guess I must have been about 12 when my dad and I made the long drive down to Throckmorton, Texas. My uncle and his brother had picked out a Galecino pony that they thought might be just right for me to do some cowboying up on our Colorado ranch east of Colorado Springs. A Galecino pony is really a horse, but only about 12 hands high fully grown as opposed to a normally sized ranch horse at 15 hands or so. However it was a breed popular among Mexican vaqueros, Dominican cowboys and just about anyone wanting a fearless, nimble and quick mount for work in and around cattle. But a little like all of Mother Natures diminutive creatures, like badgers, terriers and Shetland Ponies, a Galecino could have a powerful mind of their own.

“Go on in there, Kenny, and halter him up,” said Bob.

“OK … I guess,” I said haltingly.

“You’ll be fine. You’re a real cowboy, remember.”

At that moment, I felt like nothing could be further from the truth. I was shaking in my boots, and nearly tripped to fall face-first into the dust as I clamored over the fence. There were three horses in the corral, but Bob had made sure that I knew which one was for me. It wasn’t easy. I must have chased him up and down the fence line for what seemed an eternity, only getting a break when my dad interceded on one pass and flushed him back to a corner.

The horse was none to happy to make my acquaintance. He was even less happy to become acquainted with the saddle that I threw over his back. He quivered with the nervous twitch that you just knew was like a battery-powered spring toy ready to launch. But the saddle went on, got cinched and the bridle was surprisingly easy. This was all a ruse, of course. Like my friend Bill had often observed, this horse was just biding his time while he thought of better ways to kill me. “Time to get on up, Kenny,” said Bob.

I got my left foot in the stirrup, and this pony did what he did to me nearly a hundred more times in our 10 year relationship—he bolted. So here I go, hopping along trying to plant my right foot with enough thrust to get it over the saddle and being thwarted at every step as this belligerent pony ran the circumference of corral. How I managed to hold on to the reins I don’t know, but my left leg was darn near tearing off as I tried to mount.

We named him “Diablo” that day—not sure whether it was my idea or someone else’s, but it sure seemed to fit at the time. I owned and rode Diablo for a decade, and the more we were together, the more the memory of the disaster of our first meeting faded, and the more my respect for that valiant little cowpony grew. He probably saved my life a couple of times in front of belligerent bulls out in pasture that objected into being herded into the main corral. He got me out of storms and safely off bad trails. He ran hard in Little Britches Rodeo boot races, where he was always outgunned, and tried to be a cutting horse even though his rider was a complete amateur. Diablo almost made a real cowboy out of a little boy

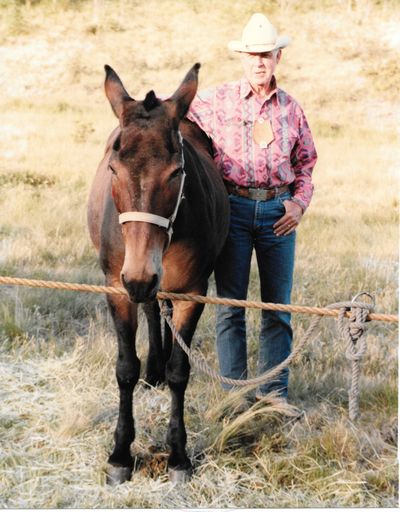

Charles and his loyal mule, Barney

Essays and Anecdotes

Every Artist Has His Own Signature

In that fateful spring when 16-year-old

Charlie Russell first arrived in Montana Territory, he came

with the desire and for the express purpose of “being a cowboy.’

Not a real “cowboy”, you understand . . .

Rather, it was to be part of a romantic dream, to relive a kind of

life that had passed into history a quarter of a century earlier.

--Ginger Renner, CM Russell’s West

The big booth at the Salinas rodeo grounds was impressively situated near the main entrance to the arena, so you knew this artist was someone to be reckoned with. The walls were filled with medium-sized watercolors of recognizable western scenes—mountain canyons and waterfalls, buckaroos on broncos, cattle drives and wintery stream crossings. I was drawn to the loose, friendly style and the arid but bright colors reminiscent of Sargent’s palette— perfectly matched to the realities of western light and color—dry, bright sunlight contacting cool purple shadows. Subtle and strong, just like the land and the cowboys who rode it.

In the middle of it all stood a famous cowboy artist, ramrod straight and every inch of what you expected was behind the brush and palette of these western scenes. His Stetson was pulled down just above the eyes and a curly blonde-gray mane poked out from behind tanned face accented by a generous mustache and goatee in perfect reverence to Wild Bill Cody. He wore slightly worn, but properly long and starched-crease denims, a big silver buckle, a bowie knife, and a turquoise bola tie to offset his old ranch hand shirt. The well-worn boots dug into the dirt and sawdust that drifted in from the rodeo arena.

But, appearances can be deceiving. Like Charlie Russell, this artist found his place in the cowboy West through a romantic artistic window long after the real West had disappeared into history. Born in Hollywood just before the war he was about as far away from a real cowboy environment as you could get. But he was the son of a cowboy film star and grew up where the cowboy legend met the silver screen. But like Charlie Russell, he had a lifelong yearning for a more legitimate experience.

He learned to ride and to ride pretty well. He rode for stunts and he acted the cowboy role like a pro. But despite the fame and relative comfort of a TV and movie career, his passion was to be an artist. Finally, well past middle age, he decided to chuck the Hollywood life and go after his dream. With one art workshop under his belt and a new ranch in Texas, he threw himself into watercolor painting with a vengeance. The results were spectacular.

I was impressed, both by the man and his work. As I turned to leave, I stopped to compliment him on what I saw.

“I love your work,” I said, “and I like to do a bit of painting myself.

But I don’t think I could ever do it as well as you do.”

Without hesitation he replied. “I’m sure you’re doing just fine. Remember, every artist has his own signature.”

I have thought about those words many times since then. Sometimes I remember his voice when I need to remind myself that what I am creating is something from my heart and my hand and that a preconceived notion of what is correct is to deny my own unique view of the world. Sometimes I repeat his words to young artists I’ve known who are doubting their own work. There are many ways to express ourselves, and trying to achieve someone else’s notion of perfection is a false hope. As Bradley Cooper’s character in the remake of A Star is Born says it: Anyone can play the notes; the important thing is having something to say.

I started drawing by accident one winter during a trip with to India. On a layover in the Munich Airport, I wandered around a gift shop with nothing particular in mind until my eyes caught site of beautifully bound leather blank book. Somehow the idea crossed my mind to try filling that book ups with little sketches of whatever I might see over the next two weeks. I drew a small map on the first page and then closed the book and put it away, not sure whether this whole idea was going to work or not.

The next entry is dated January 26, 2006 and shows three small renditions of “tuk-tuks” in New Delhi. I was off to the races. By the time our trip ended I had filled nearly every one of the little book’s 144 pages with clumsy little pencil drawings. It felt good; it felt right; and it was fun. I was forced to see—really see—the things in front of me. Each sketch was a conscious choice about the moment and the scene. Looking back at them, each sketch, no matter its technical quality, had something to say about what I was seeing and why I was drawing. Thirteen years later, I have never been without a sketchbook while we travel. I have learned to add extra tools to my repertoire, and the sketches, thanks to practice and to some good teachers, have gotten technically better. But the only ones that really stand out are the ones that have something unique to say about who or what I was seeing, and why.

There are 50 boxes of sketches that now stack up in three rows of 6 feet in my library, and an equal number of sketchbooks and folios piled up in the garage, or bedroom, or whatever random space we have for storage. I suspect that the stacks will just continue to grow, because we are not done yet with traveling, and there is still a lot I have to say about the world.

One of the author’s travel paintings - this one from a scene in a Cambodian rice field

Essays and Anecdotes

Soil Savers Christmas

The annual Soil Savers Christmas party was held each year around mid-December in the basement meeting hall of the old grange building where the monthly Soil Savers dinners would occur. The grange was located out on the east fringes of Colorado Springs, an area now covered in the concrete and glass monoliths of an abandoned mall, the city limits having moved far to the east and north of this old location now. An area that was full of open prairie homestead farms in my childhood (we used to have a milk cow staying on a farmer’s property near here, and for several years, we followed our dad out every evening to help him milk our old Betsy) had succumbed to small shops and garages, then to suburban tract housing, then to a grandiose shopping mall, and now to emptiness and abandonment. This is one of the differences I have noticed about cities and towns in the West and those I explored later as an undergraduate in upstate New York in the East. There were no natural limits to expansion in the West, and so development rolled over towns and moved on in waves until the last wave ran all the way out of town and the places left behind were emptied out again, devoid of people now, but populated by the flotsam and jetsam of past lives; people and buildings and prosperity having moved on to greener pastures. Old towns in the East were there because of particular natural constraints or favors of geography. They grew old and died like venerable oaks, not washed out and away like so much seaweed on the beach. The population changed, for sure, but the structures and their purpose largely remained. Seeing 100-year old bungalows in Denver elicits a sense of wonderment and awe. Seeing 300-year old homes in Albany hardly raises an eyebrow.

So the old grange building in 1956 captures one of the first waves of development that would was its way east and north from the old center of Colorado Springs, lapping up against the real cattle ranches that spread from here across the arid eastern Colorado plains, to just-as-arid western Kansas and finally greening up toward the rolling hills of the Heartland, away from the West and its fantastical openness and toward the close-in tamed beauty of the East. Colorado Springs had been booming from the end of the war, fueled by the return of thousands of soldiers to an area they had first seen as recruits, or had heard about from fellow soldiers—a veritable New Canaan, a land of opportunity. They came west—often fresh from colleges and universities around the country where they had been supported by the GI Bill—educated, skillful and feeling lucky to have survived.

Grandma Brown decided that service in the military service might be the only way out of a cycle of poverty and recklessness for her sons. As soon as each of her 6 sons graduated from high school, she made the trip from Cheyenne to the Denver recruiting office to deposit them in the loving care of the United States Marine Corps. Each of the Brown boys served—some in World War II, some in China during Mao’s march to victory (like my dad), some in Korea, and others in the uneasy years between Korea and Vietnam. They all went to college and graduated, most as engineers, on the GI Bill. None of them would have been able to do it otherwise.

The initial rush of GIs to Colorado Springs had begun to peak in 1955, but Colorado Springs was still benefiting from huge corollary military investments in this quiet southern quarter of Colorado. Since 1942, the huge Fort Carson complex of the US Army had hosted the 4thInfantry and Cavalry Divisions, and the original 10thMountain Division (the alpine assault troops who trained in the Rockies, fought in Europe, and whose alumni returned after the war to found the Colorado ski industry) had been housing thousands of GIs south of Colorado Springs. The Air Force Academy, with its radically modern design commissioned from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Chicago, opened in August 1954, Colorado Springs having won out in the national competition against Prescott, Arizona, Linn, Wisconsin and Alton, Illinois. A few years later, in 1961, construction was completed on the under-mountain complex called NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command), which would be joined a few decades later by the US Space Command at Peterson Air Force Base east of Colorado Springs.

The city was an unwitting but grateful beneficiary of huge federal military spending over the latter part of the 20th century, and welcomed its returning veterans with open arms. These veterans and their families helped to swell the population of Colorado Springs six-fold in the 40 years since I was born, making the city one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the country by the mid-seventies. Gratitude to the military-industrial complex, combined with a naturally patriotic attitude of western settlers, led to a relatively benign, garden-variety conservative bent in political attitudes that kept El Paso County in the traditional Republican camp for decades. But as the century wound down, I began to see evidence of an uglier xenophobic and ostensibly racist attitude abetted by the arrival of Christian evangelicals like “Focus on the Family” take root. The cowboys I knew in my youth would not have abided this view of the world, nor would the returning GIs who built this city. Some of the newcomers weren’t subscribing to true frontier values. Theirs was something alien, and way south and to the right of what I grew up with in this town. But that December night in 1955, all this growth, all this political metamorphosis, all this change was still a dream. This was still an accidental cowboy town, populated by families who did small town jobs, enjoyed the outdoors, went to parades and rodeos, and adhered to old traditions with confidence and comfort.

The Soil Saver Christmas Party was something my brother and sister could count on each year. The annual get-together was far more welcomed than Christmas Eve mass at the Episcopal church, with it interminable ups, downs and kneeling; and only slightly less anticipated than Christmas morning. The meeting hall overflowed with parents, grandparents and friends, everyone decked out in proper cowboy wear. Dads in fancy town boots and western cut suits with bolo string ties or neck scarves; moms in colorful “squaw” dresses with plenty of turquoise and silver jewelry. The kids, if their parents or grandparents took the trouble, were properly decked out the same way. Children of every age were there, perhaps thinned out a little at the teenage end, but not by much. Nervous anticipation ran high in the younger set, since the corner Christmas tree was already packed to overflow with gifts specially picked by parents for every child. Parents were relaxed and happy with kids occupying themselves, and beer, whiskey and steaks flowing freestyle.

A few minutes after dinner was cleared, a rustling near the back door signaled Santa’s arrival. How Santa miraculously appeared on East Platte Avenue, on foot, with no chimney, no apparent sleigh, and definitely no reindeer was of little concern. We were just thrilled to have him there, and ready for him to get down to business and distribute the booty. Santa had a pretty convincing costume, but I recall there was always a vague familiarity in the manner that made us think we had seen this guy somewhere before.

I couldn’t be bothered much with solving the mystery of Santa’s identity, though. I was wound up in the anticipation of the gift. What would it be? Would it be as cool as the other kids’ gifts? Did Santa really know what I wanted? Had I been “good enough” that year? I was consumed, absolutely consumed in the moment, by the gift receiving mantra of the Christmas season. The funny thing is this—as much as I was obsessed with getting a gift at the Soil Savers Christmas party—I cannot tell you today what a single one of those gifts was. After decades of Soil Savers Christmas parties, and I cannot recall a single gift. What I do remember, and very clearly, is everything else I’ve told you about the evening—the sight and smell of the Christmas tree, seeing my dad and my mom in their cowboy finest, hearing the laughter and shouting and clanking of dishes and glasses in the basement hall, running excitedly from table to table with my friends, pats on the head, hugs from grandparents, and the cold, clear night air. I can’t remember a single present I ever received. The only gifts that lasted were the memories of those unforgettable nights of family and friends.

Charter members Mark Reyner, Harold Heyse, Milt Sprenger and Clarence Coyle

Essays and Anecdotes

These Boots Are Made For Riding

Riding boots have long been a part of horse traditions in Europe, and those habits were transferred West with Spanish vaqueros in the 16th century, and gradually popularized with styles that could be massed produced in the Industrial Age, like the cavalry-styled Wellington boot that was popular among cowboys until the 1860s. Interestingly, Native Americans never saw much need for long-shafted and relatively heavy boots for riding, just as they had little need for saddles and bridled bits. Indians preferred the closer feel of mocassined feet to compliment their bareback seating and the softer control of their bitless bridles to the sterner tack of the white man. I’ve seen plenty of talented young riders handle their horses perfectly well in tennis shoes. But then, they wouldn’t be considered cowboys, would they?

American boot makers started to adapt the Wellington style to something more decorative and a little friendlier to the Spanish-derived western stirrup in the late 1800s. The western cowboy boot had a more pointed toe that slipped easily into a large and heavy leather stirrup and had a deeper heel to hold the foot in place. The longer shaft helped prevent rubbing sores on the inner calf and protect the outer leg from brush and rocks. And just to add a little spice and style for a boot that occasionally made its way to town, decorative stitching, occasional color and exotic leathers began to make their way into the designs of new boot makers like Hyer, Justin, Nocona, and Tony Lama.

I wore a long series of Justin cowboy boots of various styles and many sizes while growing up. Until I entered kindergarten, I suspect that a pair of cowboy boots was on my feet almost 100% of the time. The elementary schools in town frowned upon cowboy boots in school – not an outright ban – but they preferred kids to wear something that easily doubled as a playground shoe, and I think they were a little afraid of the damage a pointed toe boot could do in the inevitable series of schoolyard altercations.

Some of my boots fit quite comfortably, and some much less so. I wore the comfortable ones as long and as often as I could, tolerating the holes worn in the soles until even patches wouldn’t hold back the water and muck any more. I mostly owned one pair of boots at a time; there wasn’t money for separate pairs of work boots and dress boots. Later on, with my own money, and confident that my feet would stop growing one size per year, I owned two pairs of boots at a time – one dressy and one for real work. The work boots always felt more comfortable than the dress boots. Heels too high, arch to sharp, toes too narrow gave me enduring sympathy for women and their shoes.

It turns out that one of the great things about cowboy boots for a person with feet like mine is the fit. The boot has a natural tendency to go long and narrow – it just seems to be part of their DNA. A good pair of cowboy boots that fit my size 14 AA foot like a glove. My current pair of Justin working boots—plain, slightly round toe, unadorned solid cowhide and thick and durable soles—are my longest serving, most reliable and truly comfortable pair of footwear that I own. I feel particularly good when I wear them, which is nowhere near as much as I would like to. Putting on those boots is a part of my Colorado tradition. Just like my hat, it pulls in the fresh cool air, the sounds of rushing Blue River water, the wind jostling the aspen leaves, the sound of the screeching red-tailed hawk. Somehow the ground seems more comfortable in these boots, more steady underfoot. I feel a good 6” taller in my boots. That is a blessing in my late 60s.

Sketch by author from the Range Ride

essays and anecdotes

In Good Company

There is a common saying that goes something like this “you are the company that you keep.” The same sentiment is expressed in many languages, and in many cultures, over years and years of human history. Jose Andres, the celebrity chef, recently cites the saying in Spanish “Dime con quien andas y te dire quien eres” – Tell me who your friends are and I’ll tell you who you are. For Jose Andres, such a friend was Anthony Bourdain. For my father, there were many men, but chief among them were Don Norgren, Harlan and Ken Ochs, Bob Read and Terry Harris.The people with whom you associate are indicative of your character and values, otherwise, why would they be such an important part of your life? I have seen it play it out in my father’s life and in my own. Our choice of friends is important. We may not be able to choose our family—but we can definitely choose those we associate with and build our lives around. My father’s choices are a perfect illustration.

Site Content

The Cowboy Myth

Charles’ youth was surrounded by the mystique of the American Cowboy, even though the real cowboy era had faded into history nearly four decades earlier. In the decade between 1920 and 1930, western films reached their zenith, peaking in 1925 with the production of “The Vanishing American”. Westerns challenged both Romance and Comedy for most popular genres during those years. The production of classic western films continued at a steady rate (10% of all films produced) through the 1950’s, but then saw a steady decline after 1955. Today, the classic western comprises less than 0.5% of all movies produced worldwide. And yet, the American Cowboy myth persists.

A similar pattern can be found in the music world, but cowboy nostalgia seemed to linger a bit longer than in the film world. True to the independent spirit attributed to the cowboy persona, the song “Don’t Fence Me In”, written in 1934 by Robert Fletcher (lyrics) and Cole Porter (score), and sung by Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters, hit No. 1 on the Billboard charts for three months in late 1944 and early 1945. Later on, Roy Rogers sang the song in two movies—Hollywood Canteen (1944) and Don’t Fence Me In(1945)—accompanied by the Sons of the Pioneers, my grandfather’s favorite ensemble. Kate Smith—of God Bless America fame—sang the same song on an October 1944 radio broadcast.

It was a special and very American tendency to make heroes out of frontiersmen even as they were still alive and burnishing their legacies. Steve Inskeep, in his book Imperfect Union about the lives and adventures of John Charles Fremont before the Civil War, writes about the way that legend and current events melded together in the media of the day. As his reviewer, Adam Gopnik puts it:

The American frontier, the Wild West, was not burnished and made epic in memory. It was made epic even as its very brief life was taking place. Buffalo Bill was only twenty-three when dime novels about him began to appear in New York … Billy the Kid’s life read like a ‘press agent’s yarn’ … and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were robbing banks and posing for mock formal photographs all at the same time.

Charles Brown, Range Rider and occasional Cowboy

My Blog

Copyright © 2019 Accidental Cowboy - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy